To The counsellor I went to speak to in March 2014,

You may never see this letter, you may not even remember me. But make no mistake that I remember you.

In my first year of university, when life was unbearable and I had nothing left to give, I went to you for help. I gathered the last vestiges of my resolve and forced myself out of the bed I hadn’t left for six days to attend the appointment I’d already rearranged with you twice.

I remember sitting on the chair in your office, my cane in one hand and a box of tissues you’d handed me in the other, feeling empty; feeling dead; feeling black. I remember the nervousness with which you guided me to my chair and your uncomfortable laugh when I explained that you would need to complete your survey with me as I wouldn’t be able to write my answers myself.

You asked me to wrate my feelings on a scale, zero being not at all and 10 being all the time. I remember being surprised at my own answers when I responded to statements such as, “I feel hopeless or worthless” never scoring less than 7.

I knew I was in trouble, that’s why I went to you. I knew that staying in bed for over a week was not normal. I knew that missing countless lectures and cancelling numerous appointments for fear of leaving my room was not normal. I knew that ignoring phone calls and messages from concerned loved ones to avoid admitting what I was doing was not normal. I knew that a black cloud had gripped me, and I went to you to give it a name.

When you ask me why I was there, I told you everything. In a monotone voice and divoid of emotion. Continuous obstacles and injustices had warned me down to the point that the only thing left was anger, and as I told you what had happened during the last few months and how it had made me feel I think you saw how much that anger was consuming me.

I told you how the support I had expected had not been delivered. I told you that I felt isolated and unable to identify with my peers. I told you how, despite feeling unable to leave my room for the last 10 days because of the anxiety that gripped me at the thought of interacting with people, I didn’t want to give in. I told you that I wanted to be there. I told you that I wanted a degree. I told you that I wanted to prove myself, to myself and to the world.

I wanted you to offer me support, to tell me that it was normal for me to feel this way and that the way I had been treated was unacceptable. I wanted you to tell me that my feelings were justified and that it wasn’t my fault. I wanted you to reassure me that you understood, that I hadn’t failed. But you didn’t.

Instead you told me that “maybe University might not be the right place for me”. You suggested that perhaps I should consider dropping out of my degree, as I had confided in you that I was so close to doing. You admitted that maybe I would be better off going home and giving up.

Thank God I ignored you.

You telling me that I shouldn’t be at university only rekindled the determination in me that had been stamped out by repeated disappointment. Your words rang in my ears and reverberated around my head for months, years afterwards. Your pitty and doubts in my ability became the fuel that only drove me to push myself harder; to get myself better; to believe in my self because you didn’t.

You are not alone in thinking that people like me are not worthy or not capable of achieving. The cane in my hand predisposed you to judge me before I had even started speaking, as it does for so many people in society. Those of us living with disabilities continuously face the misconceptions and misunderstandings of those who do not live with our challenges. But this attitude extends wider than just speaking to my friend rather than me when we are out, or ignoring my refusal of the help you have offered. This attitude leads to systematic failures that put barriers in the path of people like me from living normal lives and achieving our goals.

Every time you take me by the arm and lead me somewhere I don’t want to go without my consent, you undermine my autonomy and disrespect my personal space; every time you fail to provide me with material in an accessible format, you reinforced the feeling that I and my needs are an afterthought; every time you tell me, that because of the adaptions I need, I am being difficult and giving you more work than you already have, you are reiterating the message that I am not welcome. I am not worthy of the time and effort it would require you to include me. I am an inconvenience that should be reprimanded for having the audacity to expect to be given the same opportunities as those who don’t need The adaptions necessary for me.

You epitomised this attitude for me, and as a result you made me stronger. Your ignorance reawakened and the stubbornness that defines so much of my character, not because it is part of my nature, but because it has to be. Your audacity to suggest that I would be better off giving up on my dream, despite me specifically explaining to you that this wasn’t what I wanted, thickened my skin and hard and my resolve to prove you wrong.

For so long your words were my motivation, though a part of me still believed you. So when, in my third and final year, everything again became too much and I threatened to crumble beneath the pressure to disprove your assumptions, your words again reverberated in my head and convinced me of their truth.

But you didn’t win. I did. This time when I asked for help I received the reassurance and support you denied me. With that support I was able to again pull myself out of the darkness and overcome the final hurdle that would get me to my goal.

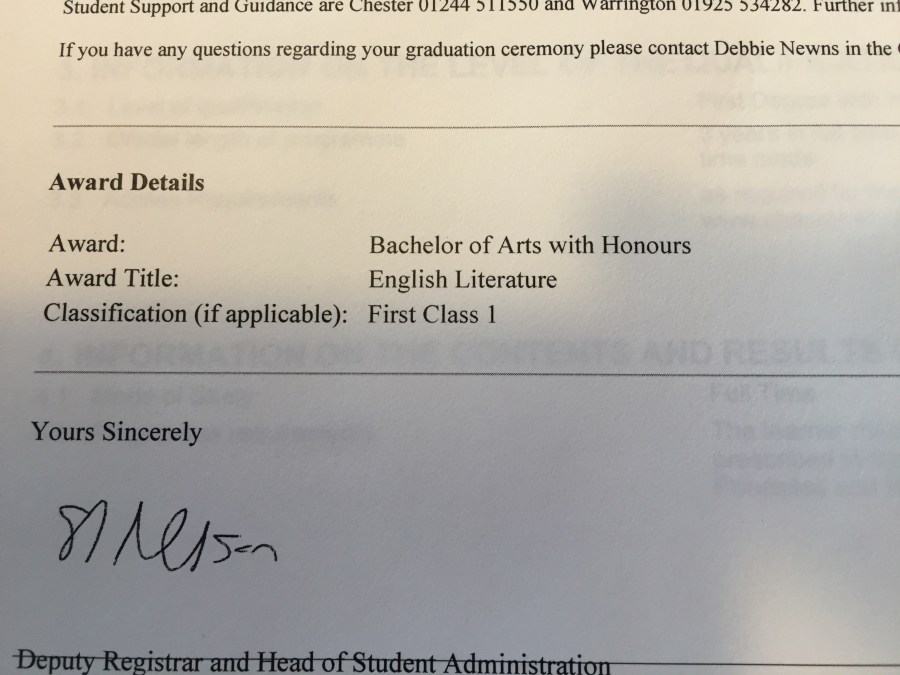

I am graduating with a first class honours, because of you. Whether it was your intention or not, your words have gotten me through the last three years and helped me achieve what I always hoped I could do but often thought was impossible. So I want to thank you for meeting me that day and for judging me as so many others do, because in doing so you gave me a reason to make myself and everyone around me proud. You forced me to find the self belief and self-worth I had lost, you shocked me out of my depression and inspired me to be the person I knew I was, but that you were too blind to see.

Thank you for giving me the strength to prove my capabilities to anyone who doubts me. Thank you for motivating me to do my absolute best to show exactly what I can do. Thank you for reminding me that I alone can determine my worth. Thank you for having such low expectations of me and challenging me to exceed them. Thank you for inspiring me to continue facing my challenges head on and reminding me why I thrive on doing so. Thank you for teaching me that my disability doesn’t define me, and that it is my responsibility to demonstrate this to anyone who thinks otherwise. Thank you for reminding me why I wanted a degree in the first place. Thank you for driving me to work so hard that I not only exceeded your expectations, but also exceeded my own.

Thank you, in short, for ignoring my own words and deciding my capabilities based on your judgement of my disability. Because in doing so, you’ve reminded me that nobody has the right to decide my limitations but me.